Executive summary

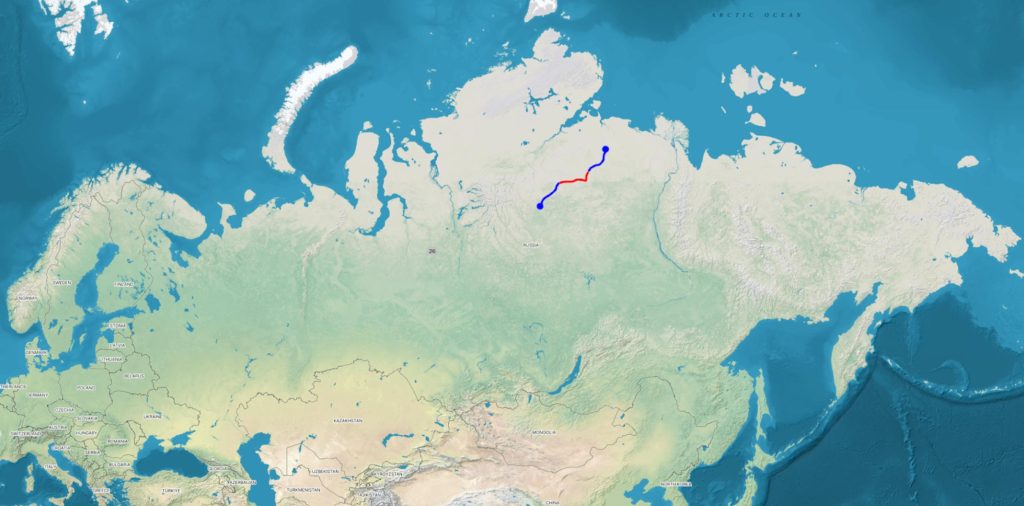

A solo winter traverse (second half of February) of the Anabar Plateau, the most remote part of the Central Siberia Plateau. The first ever traverse in deep winter.

About the region

The Anabar Plateau is the northernmost part of the Central Siberian Plateau. Along with certain sections of the Putorana, Syverma, Tunguska, and Vilyuy Plateaus, it forms the most remote and least explored region of this vast upland.

There is no infrastructure on the plateau, no roads, trails, paths, or even informal tracks. The only exception is a single, abandoned and crumbling geological outpost located in the north-central part of the region.

Access to the plateau is extremely limited. The four primary entry points are the villages of Saskylakh (northeast), Olenyok (southeast), Khatanga (northwest), and Yessey (southwest). All of them lie far beyond the actual boundaries of the plateau.

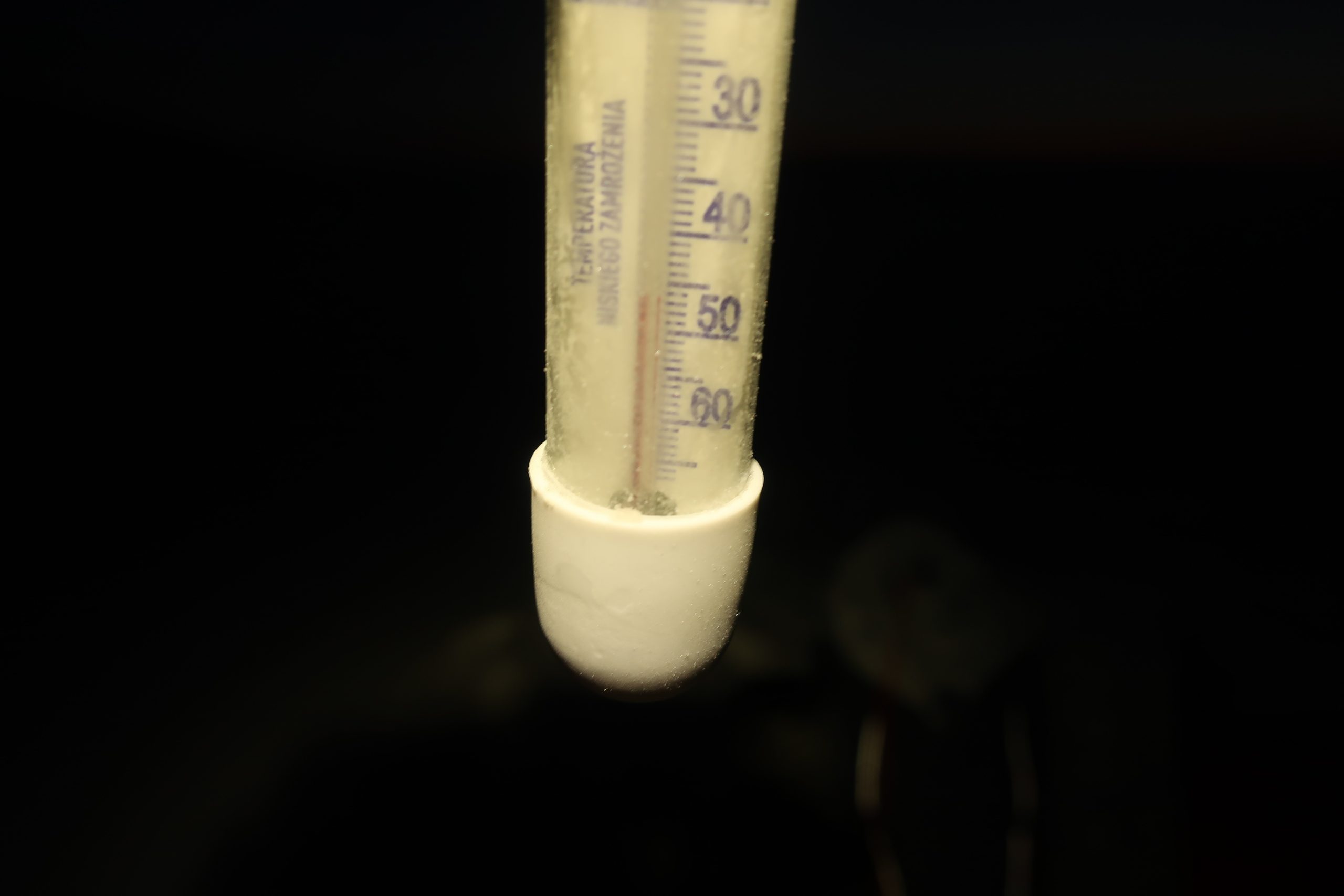

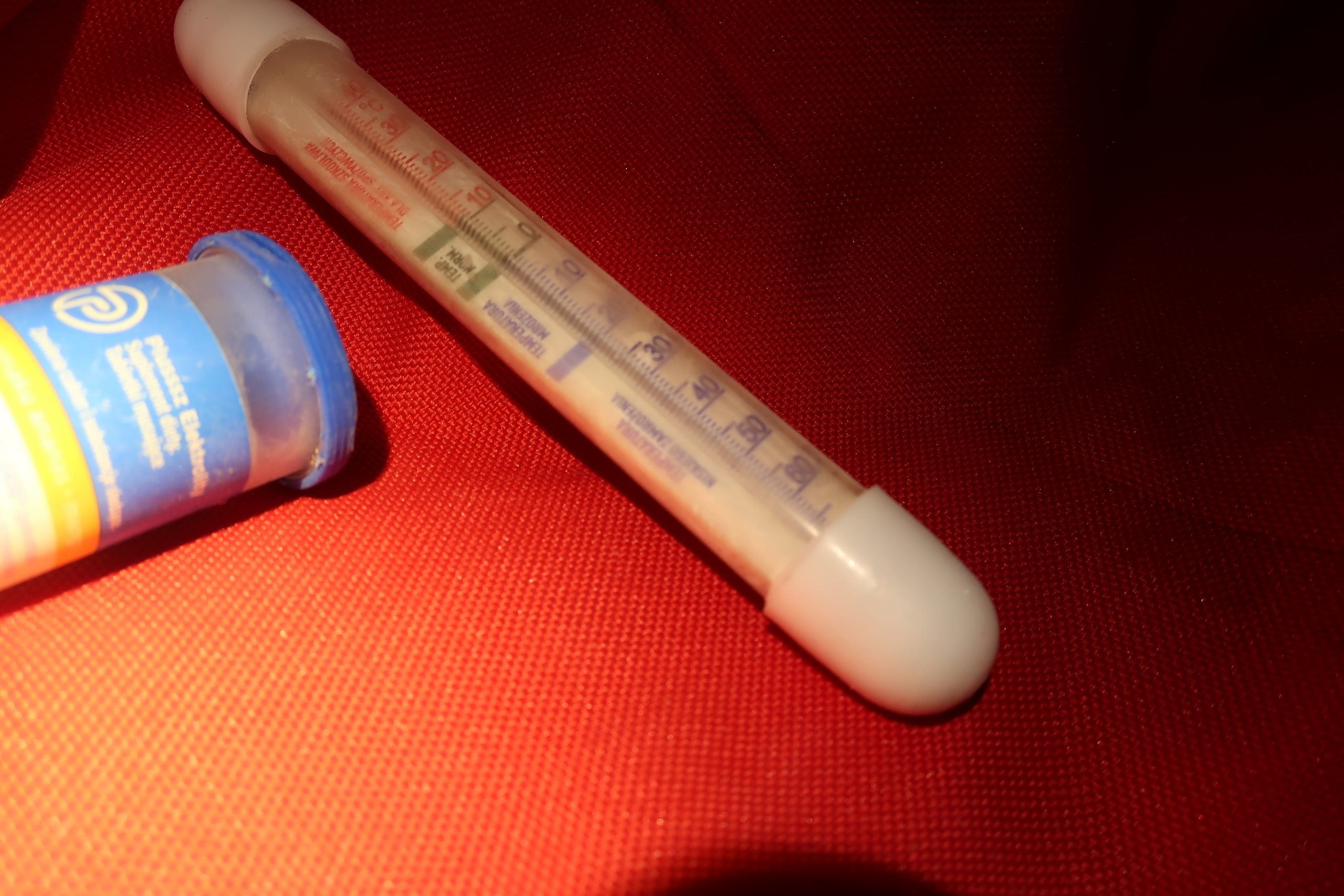

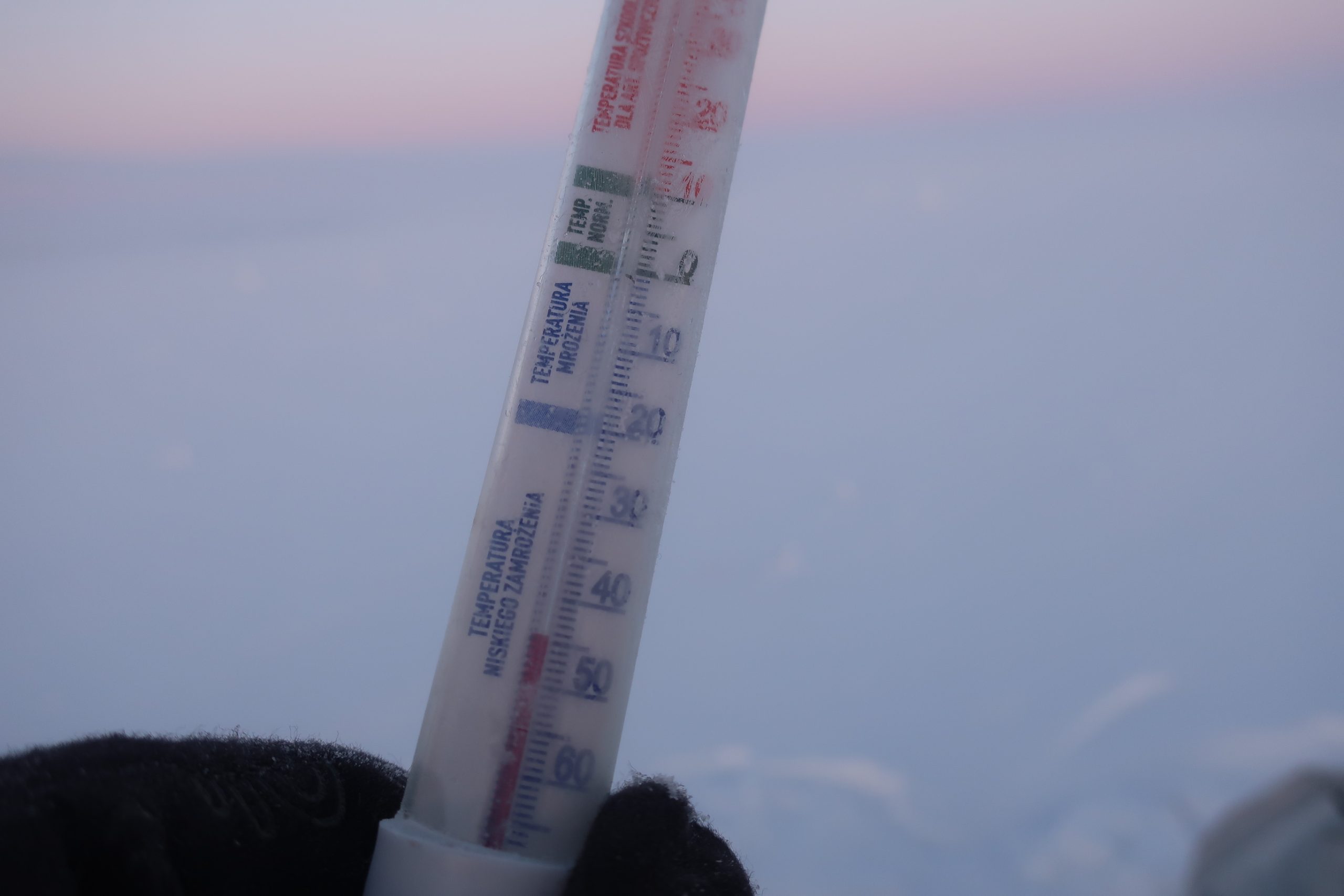

Anabar Plateau belongs to the coldest part of Siberia, with January-February temperatures regularly dropping to -50 C for weeks, with lowest reaching -60 C.

Earlier expeditions

My expedition was most likely the first in history to explore this region not only during the meteorological winter but also largely within the calendar winter period.

Prior to this, there were only two known winter expeditions to the Anabar Plateau:

- The first was organized by a large team (9 people) in 2011 (report). They wrote (translation via Google Translate): “As far as we were able to find out, there had been no previous winter visits to this region. Thus, by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the Anabar Highlands remained one of the last polar mountain regions (…) untouched by ski and trekking tourism.”

- The second expedition – solo – was conducted in 2022 (report). He notes (translation via Google Translate): “In 2011, under the leadership of Anton Chechetiani, the first ski expedition of the highest—6th—category of difficulty was completed: a linear route from the village of Khatanga to the village of Olenyok in 35 days (…) Since then, no ski tourists have visited Anabar, and no other winter accounts could be found.”

Andrey began his expedition on March 10, while the 2011 group set out on March 17. I completed my crossing in February. On the other hand, my route was shorter than both previous expeditions. This was partly due to uncertainty about whether and where I would be able to meet with a transport team from the village of Yessey after crossing the plateau (details below).

It’s worth noting that even in summer, expeditions to this region are exceedingly rare. I am aware of only two documented summer crossings of the plateau, one in 2013 (report) and my own in 2022, which was likely the first solo summer traversal.

Goals

Objective 1

Solo crossing of the Anabar Plateau, especially its southern highlands, in deep winter (January–February).

These “highlands” are a rugged, stone-strewn region rising above the surrounding tundra, characterized by heavily undulating terrain. I reached the starting point on the southeastern edge of the plateau via snowmobile from the village of Saskylakh, approximately 300 km over frozen rivers, a journey that took 2.5 days.

From there, I proceeded on skis almost directly west and southwest. In the first part, I climbed the highest point of the plateau. In exactly the mid point of the expedition, a few days after that, I climbed an interesting peak (details below). Upon completing the crossing and reaching the southwestern edge of the plateau, I was picked up by two hunters who had barely managed to reach me from the village of Yessey, located roughly another 250 km farther to the southwest.

Objective 2

Ascents of two summits/points:

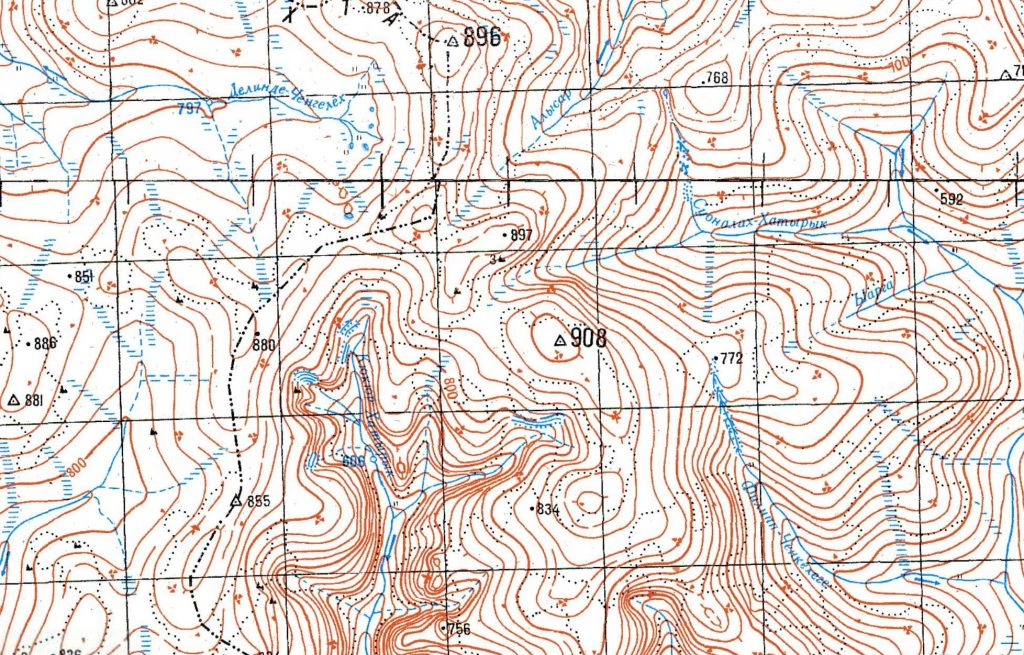

The first was the highest unnamed point on the plateau (I refrain from calling it a summit as the terrain is extremely flat). On old Soviet military maps, its elevation is marked as 908 meters. This was the first recorded winter (both calendar and meteorological) ascent. The topographic profile (Topomapper layer) can be viewed here: map link.

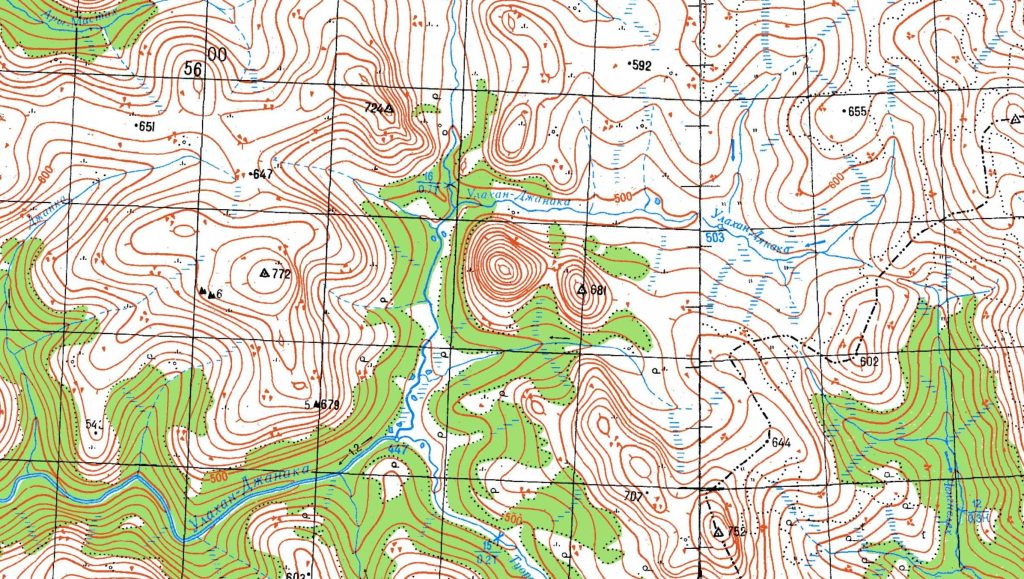

The second was a genuinely interesting peak I had identified a few years ago during a detailed analysis of the plateau’s topography. Located roughly 70 km farther to the southwest, in the south-central part of the plateau (map link), it stands out on the profile – unlike almost all other uplands in the region, it appears steep, like a real mountain. It has no name, no marked elevation, and when I reached the summit, there was no geodetic marker – this may well have been a completely virgin peak. I made a quick ascent as part of a one-day excursion from my tent. Thanks to the presence of sparse forest in the area, the outing felt almost like a spontaneous ski-tour in the Beskids.

Interesting situations & stories

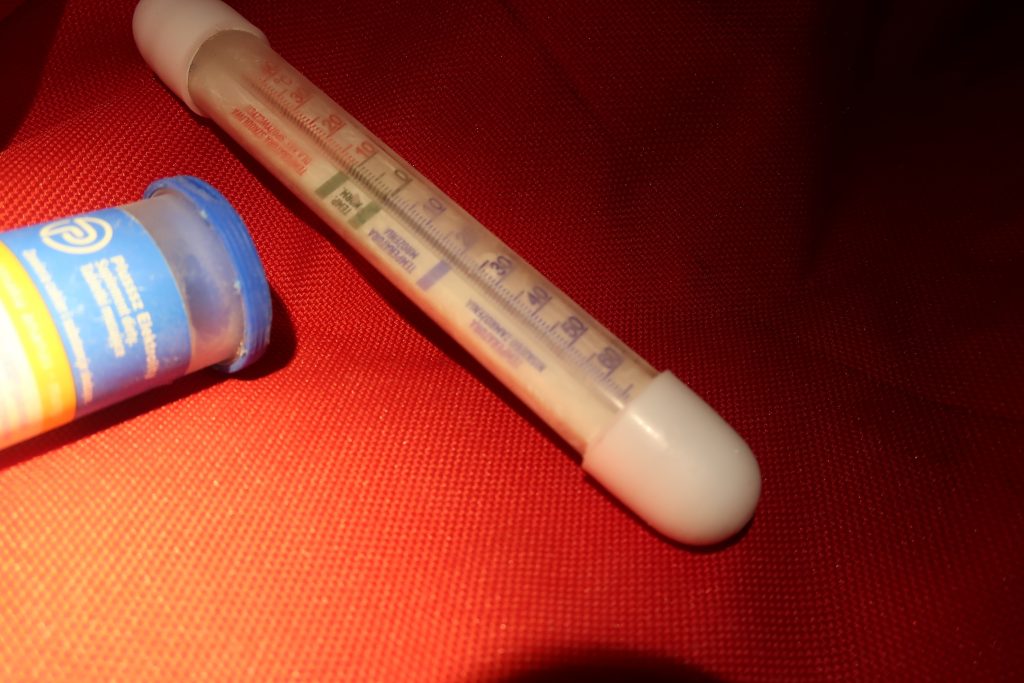

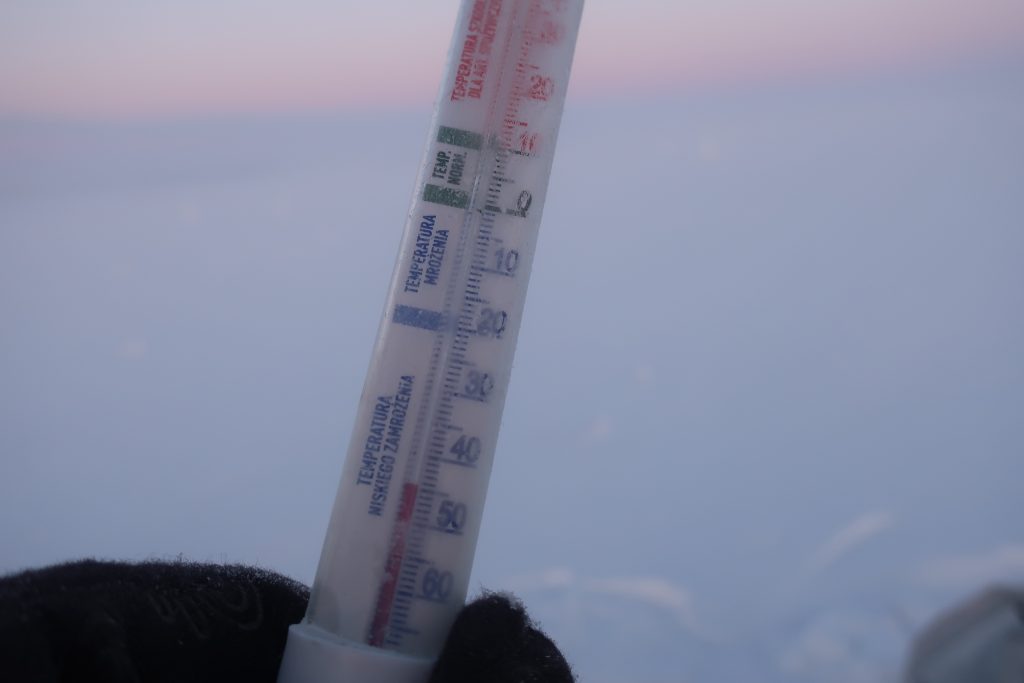

Temperatures. Temperatures (absolute) began around -40°C in the afternoons and dropped further—typically to around -45°C in the late mornings, and down to -50°C at night. The warmest moments rarely exceeded -37°C, and even then, only briefly.

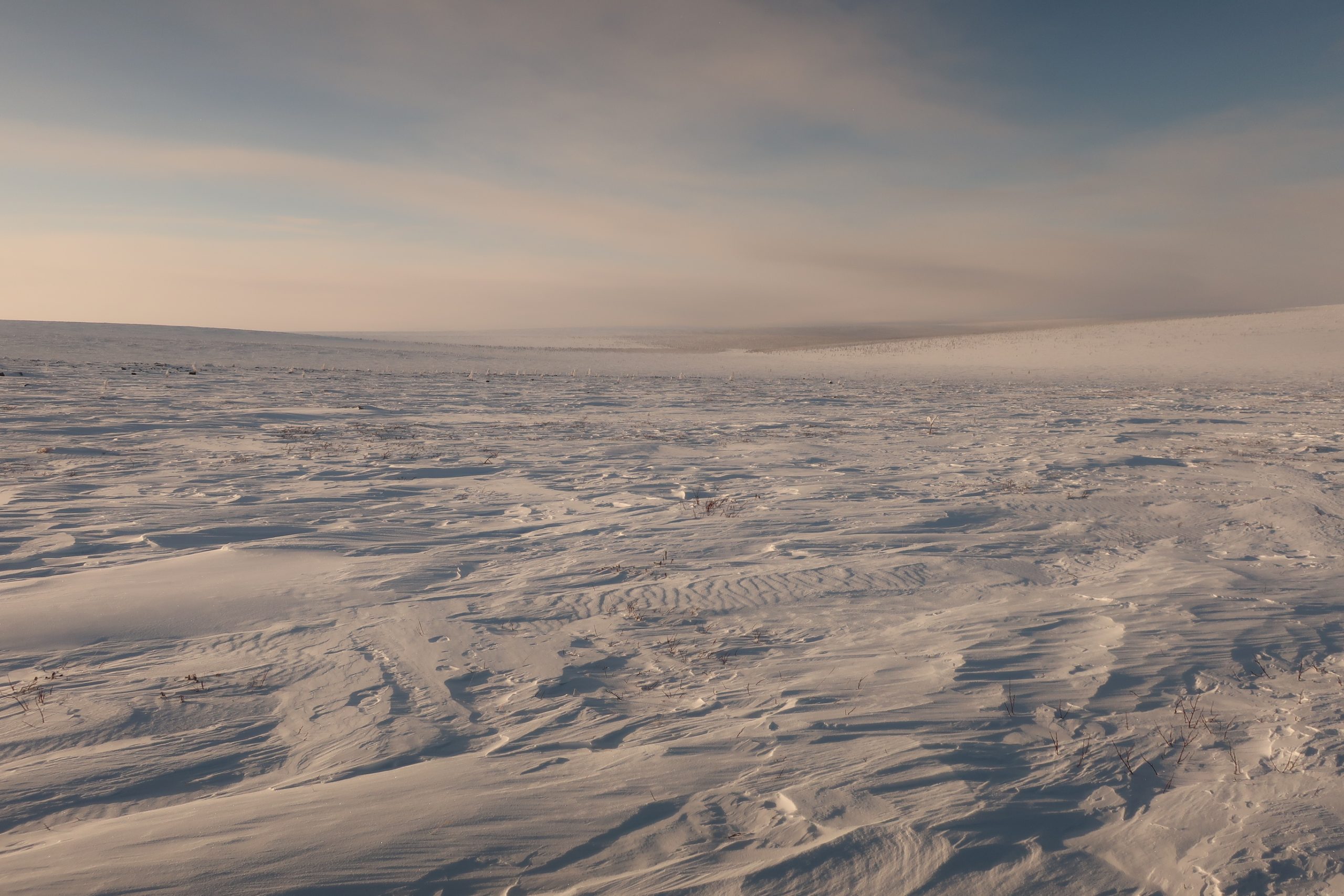

Strong winds. Winds persisted through more than half the expedition.

Purga. Near the end of the journey, I encountered a powerful Siberian storm system known as the purga (Buran), characterized by violent, frigid air masses and hurricane-force gusts. During this phase, absolute temperatures hovered around -40°C, intensified by fierce winds, which means the windchill effects of down to -70°C. Thankfully, these were mostly crosswinds, though I was knocked down several times. Often, I was skiing and setting up camp half blindly in the evenings, as my eyelashes froze to my cheeks. I chose to continue pushing through the purga rather than wait it out, because although the village of Yessey (my endpoint) does have occasional helicopter access, flights are infrequent. I hoped to reach the village in time for one scheduled to arrive within the following 10 days.

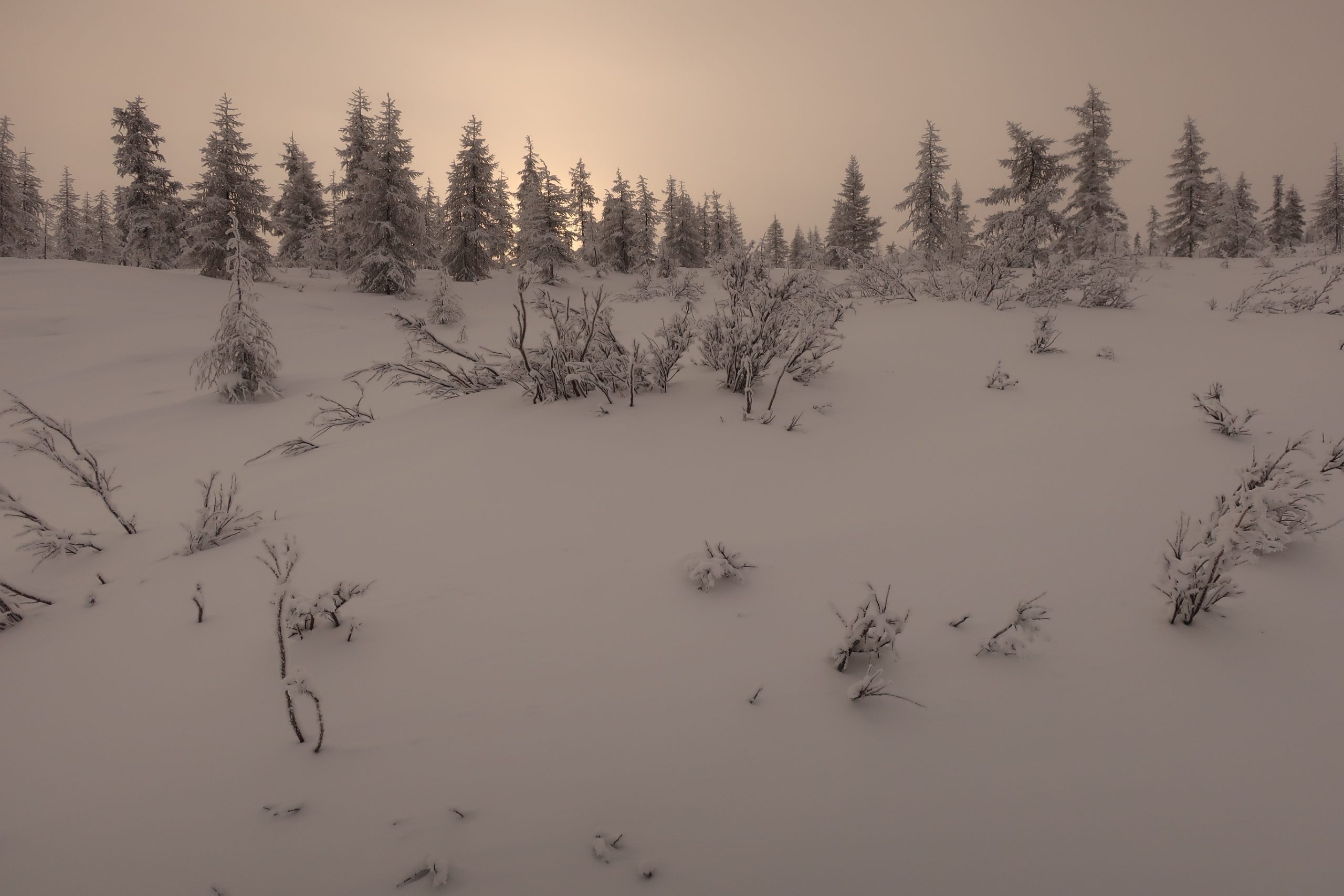

Deep snow. I planned my route using old Soviet military maps supplemented with more recent satellite imagery. As with all my expeditions, I had to prepare and calculate everything entirely on my own, there was no one to consult regarding route specifics. Both earlier ski expeditions had followed a diagonal route from the northwest (from Khatanga) to the southeast (to Olenyok or Saskylakh). In contrast, my path ran through the completely untouched southwestern part of the plateau, where no previous winter expeditions had ventured. In the southern reaches, where taiga forest begins to appear, I had to plan carefully to avoid areas of soft, deep snow. The maps proved inaccurate, and I spent several days moving through unexpectedly dense forest and soft, deep snow.

Uncertainty. Throughout the journey, I carried the mental weight of uncertainty: there was a real chance that the transport from Yessey would not reach me, forcing me to continue alone through deep snow and forest to the village for 150+ kms, a scenario that would have pushed my supplies to the absolute limit and beyond. The hunters from Yessey had agreed to attempt to reach me, but:

(1) the early winter had been exceptionally snowy, making travel extremely difficult, and

(2) they had never been to this area before (to my knowledge, no one from Yessey had ever ventured into this part of the plateau in winter; their usual hunting routes lead in different directions).

Reaching me by snowmobile was difficult because the only viable routes ran along frozen rivers. These were interrupted by canyons, thick forest, rock fields, exposed stone, and naleds, i.e., layers of ice fractured from below under immense hydraulic pressure, making the journey uncertain and hazardous. Ultimately, it took them five days to reach me.

I also planned the route for the Yessey team myself, which proved to be virtually the only feasible pickup corridor.

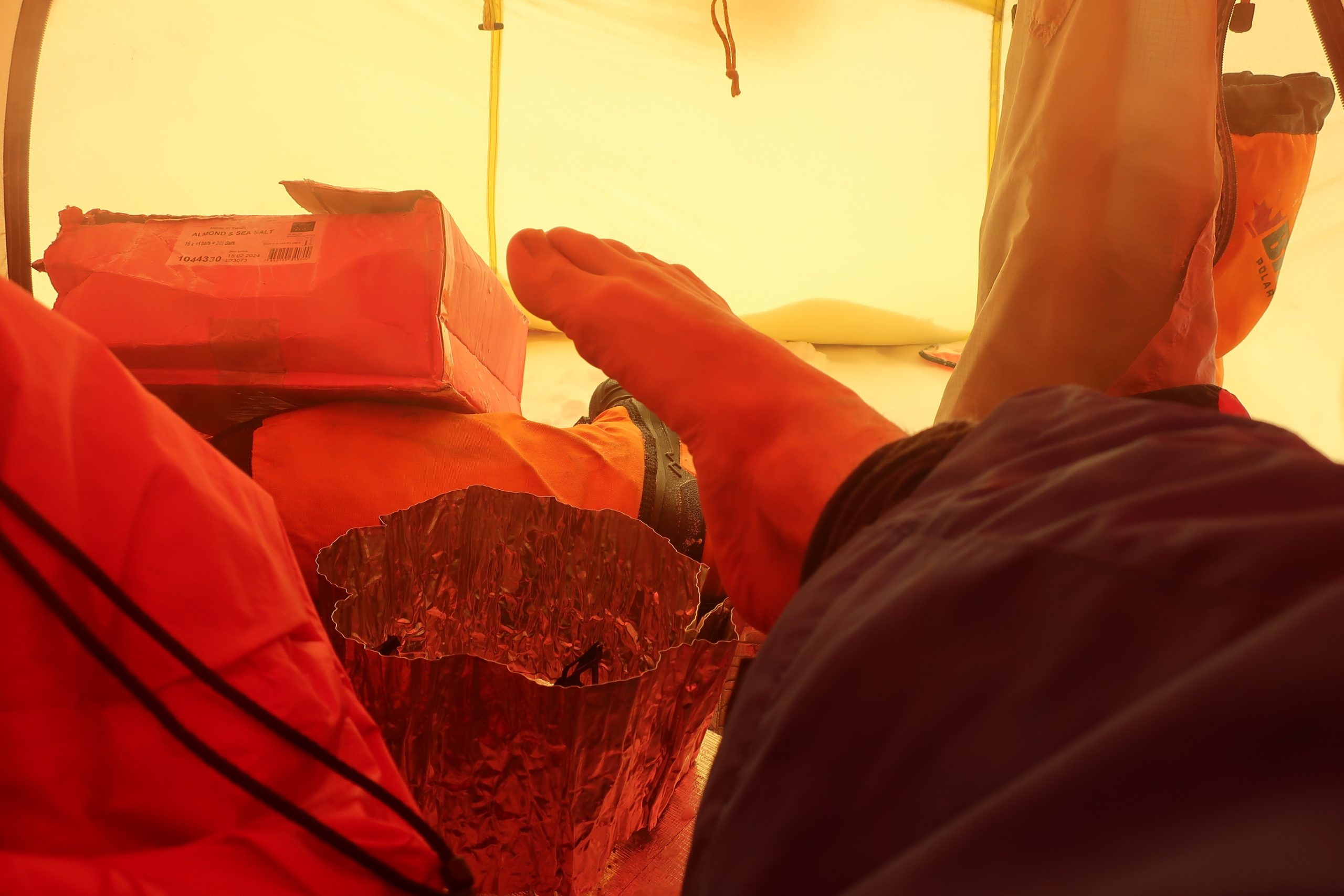

Pain in fingers. This time, I was more determined than usual to ensure we succeeded in meeting, rather than dragging my sled through the forest, because I had begun experiencing intense pain in all ten fingers toward the end of the expedition. While I avoided frostbite (I’m extremely careful), I had probably overestimated my circulation and likely spent too long exposing my hands to the cold in gloves rather than switching to thick mittens, especially when working around the tent.

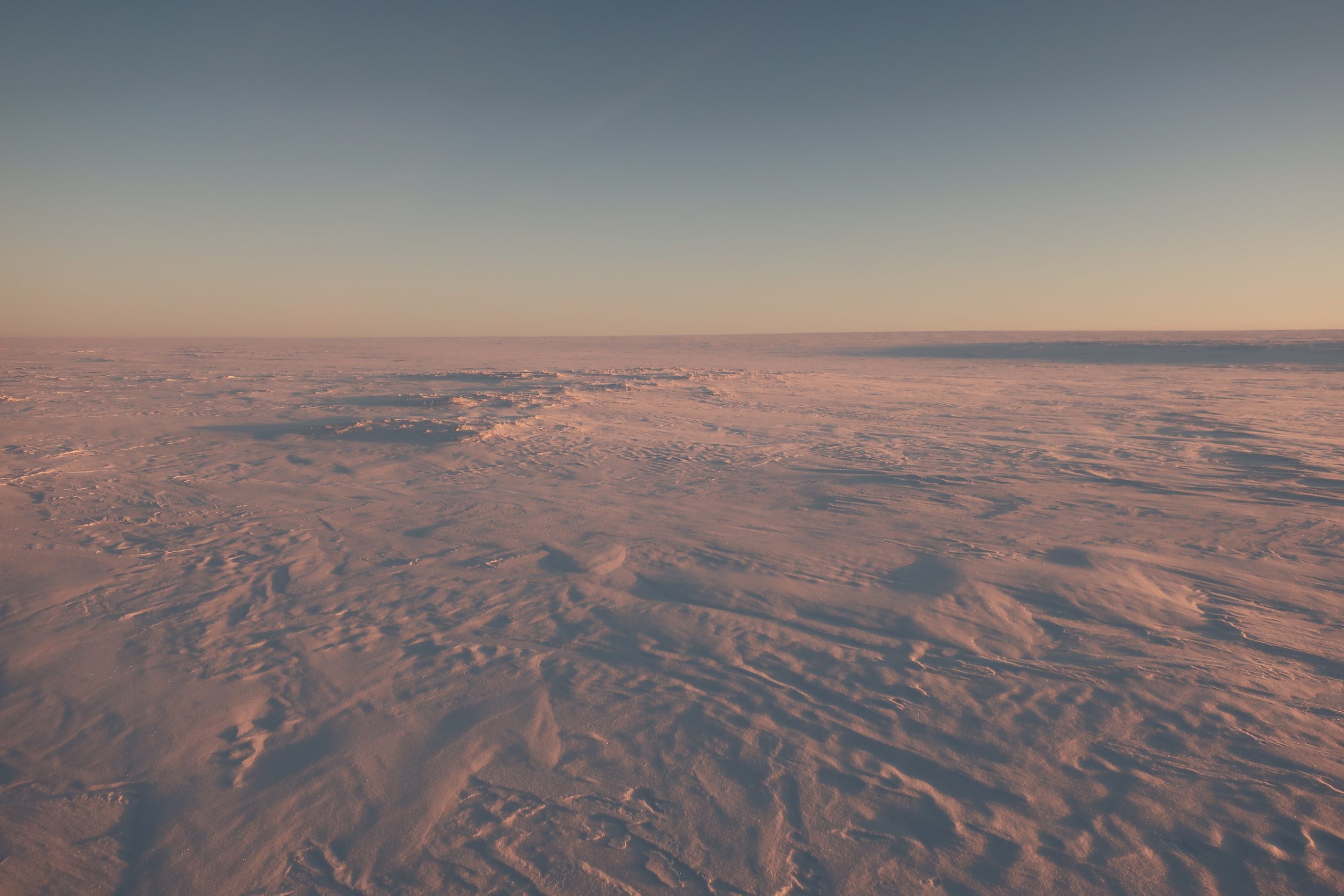

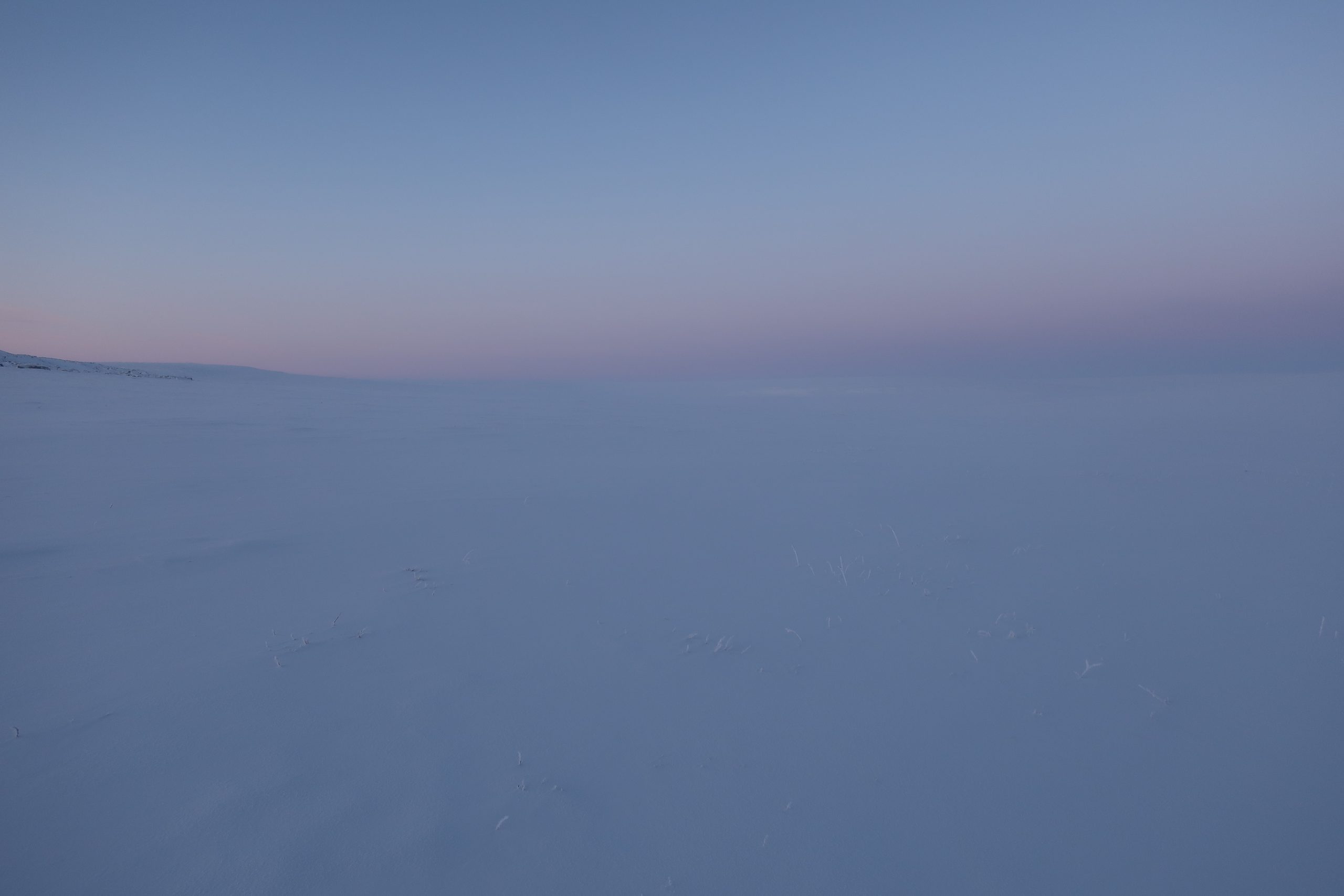

Terrain & topography. The terrain was highly varied, as seen in the photographs: tundra, stone fields, river valleys, passes, taiga forest, slopes.

Avalanches. There were a few sections where avalanche risk was present, particularly on steeper terrain.

Stone & bare rock fields. The stone fields were particularly challenging—constantly wind-scoured, with almost no snow cover and razor-sharp rocks everywhere. I was using Paris-style sleds (pulkas), so I had to carefully maneuver to avoid damaging them. It felt a bit like moving through a minefield, as the rocks were often hidden beneath a thin layer of snow—constant vigilance was required.

Compass problems. The Anabar Plateau has another unique characteristic I had already encountered during my summer traverse in 2022 (and which others have also noted): the compass frequently shows incorrect headings. This is most likely due to localized metallic ore deposits. My compass malfunctioned multiple times throughout the expedition.